Human Papillomavirus Vaccines: Questions and Answers

What are human papillomaviruses?

Human papillomaviruses (HPV) are a group of more than 100 viruses. They are called papillomaviruses because certain types may cause warts, or papillomas, which are benign (noncancerous) tumors. The HPVs that cause the common warts that grow on hands and feet are different from those that cause growths in the throat or genital area. Some types of HPV are associated with certain types of cancer. These are called “high-risk†oncogenic or carcinogenic HPVs.

Of the more than 100 types of HPV, over 30 types can be passed from one person to another through sexual contact. Although HPVs are usually transmitted sexually, doctors cannot say for certain when infection occurred. About 6 million new genital HPV infections occur each year in the United States. Most HPV infections occur without any symptoms and go away without any treatment over the course of a few years. However, HPV infection sometimes persists for many years, with or without causing detectable cell abnormalities.

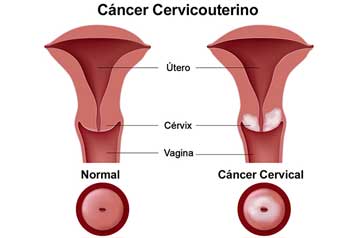

Do HPV infections cause cancer?

Infection with certain types of HPV is the major cause of cervical cancer. Almost all women will have HPV infections at some point, but very few will develop cervical cancer. The immune system of most women will usually suppress or eliminate HPV. Only HPV infections that are persistent (do not go away over many years) can lead to cervical cancer. In 2006, an estimated 10,000 women in the United States will be diagnosed with this type of cancer and nearly 4,000 will die from it. Cervical cancer strikes nearly half a million women each year worldwide, claiming more than a quarter of a million lives. Studies also suggest that HPVs may play a role in cancers of the anus, vulva, vagina, and some cancers of the oropharynx (the middle part of the throat that includes the soft palate, the base of the tongue, and the tonsils). Data from several studies also suggest that infection with HPV is a risk factor for cancer of the penis.

Can HPV infection be prevented?

The surest way to eliminate risk for genital HPV infection is to refrain from any genital contact with another individual.

For those who choose to be sexually active, a long-term, mutually monogamous relationship with an uninfected partner is the strategy most likely to prevent genital HPV infection. However, it is difficult to determine whether a partner who has been sexually active in the past is currently infected.

It is not known how much protection condoms provide against HPV infection, because areas not covered by a condom can be infected by the virus. Although the effect of condoms in preventing HPV infection is unknown, condom use has been associated with a lower rate of cervical cancer, an HPV-associated disease.

Recently, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a vaccine that is highly effective in preventing persistent infection with types 16 and 18, two “high-risk†HPVs that cause most (70 percent) cervical cancers, and types 6 and 11, which cause virtually all (90 percent) genital warts (1).

What preventive HPV vaccines are available?

In addition to the newly approved HPV vaccine, another promising vaccine is in the late stages of clinical testing. Both are based on technology developed in part by National Cancer Institute (NCI) scientists. NCI licensed the technology from this discovery to two pharmaceutical companies—Merck & Co., Inc. (Merck) and GlaxoSmithKline (GSK)—to develop HPV vaccines for widespread distribution. The FDA recently approved Gardasil™, the vaccine produced by Merck. It is called a quadrivalent vaccine because it protects against four HPV types: 16 and 18, the types that account for about 70 percent of cervical cancer worldwide, and 6 and 11, the types most commonly associated with genital warts. Gardasil is given through a series of three injections into muscle tissue over a 6-month period.

The other promising vaccine, Cervarixâ„¢, is produced and is being tested by GSK, but is not yet approved by the FDA. This vaccine is called a bivalent vaccine because it targets two HPV types: 16 and 18. Early findings have shown that this vaccine also protects against persistent infection with these two types of HPV. It is also given in three doses over a 6-month period.

Neither of these HPV vaccines has been proven to provide complete protection against persistent infection with other HPV types, including other types that cause cervical cancer. Therefore, about 30 percent of cervical cancers and 10 percent of genital warts will not be prevented by these vaccines. In addition, the vaccines do not prevent other sexually transmitted diseases, nor do they treat HPV infection or cervical cancer.

Because the vaccines will not protect against all infections that cause cervical cancer, it is important for vaccinated women to continue to undergo cervical cancer screening as is recommended for women who have not been vaccinated.

How do HPV vaccines work?

The HPV vaccines work like other immunizations that guard against viral infection. The investigators hypothesized that the HPV’s unique surface components might create an antibody response that is capable of protecting the body against infection, and these components could be used to form the basis of a vaccine. These surface components are virus-like particles (VLP) that are non-infectious and produce antibodies that can prevent the complete papillomavirus from infecting cells. They are thought to protect primarily by causing the production of antibodies that prevent infection and the development of those cervical cell changes seen on Pap tests that may lead to cancer (2). Although these vaccines prevent HPV infection, it is not known if they can eliminate existing cervical cell changes due to HPV.

How effective are the HPV vaccines?

These two vaccines are highly effective in preventing infection with the types of HPV that they target. The vaccine approved by the FDA (Gardasil) prevented nearly 100 percent of the precancerous cervical cell changes caused by the types of HPV targeted by the vaccine for up to 4 years after vaccination.

Why are these vaccines important?

Widespread vaccination has the potential to reduce cervical cancer deaths around the world by as much as two-thirds, if all women were to take the vaccine and if protection turns out to be long-term. In addition, the vaccines can reduce the need for medical care, biopsies, and invasive procedures associated with the follow-up from abnormal Pap tests, thus helping reduce health care costs and anxieties related to abnormal Pap tests and follow-up procedures (2).

How safe are the HPV vaccines?

Before any vaccine is licensed, the FDA must determine that it is both safe and effective. Both vaccines have been tested in thousands of people in the United States and many other countries. Thus far, no serious side effects have been noted. The most common problem has been brief soreness at the site of injection and other local injection site symptoms commonly experienced with other childhood vaccines.

How long do the vaccines protect against infection?

The duration of immunity is not yet known. Research is being conducted to find out how long protection will last. Studies thus far have shown that Gardasil can provide protection against HPV 16 for 4 years. Studies with the bivalent vaccine produced by GSK showed protection from infection with both HPV 16 and 18 for more than 4 years.

Will booster vaccinations be needed?

Studies are under way to determine whether a booster vaccination is necessary.

Who should get the HPV vaccines?

The vaccines are proven to be effective only if given before infection with HPV, which would be before an individual is sexually active. The FDA-licensing decision includes information about the age and sex for recipients of the vaccine. For Gardasil, the age range is 9 to 26 years.

After a vaccine is licensed by the FDA, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) makes additional recommendations to the Secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) and the Director of the centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) on who should receive it, at what age, how often, the appropriate dose, and situations in which it should not be administered. ACIP is made up of 15 experts in fields associated with immunization. ACIP provides advice on the most effective ways to use vaccines to prevent diseases. ACIP recommendations are not binding but are usually followed by health care professionals and often influence insurance reimbursement. More information about ACIP can be found on the CDC Web site at http://www.cdc.gov/nip/ACIP/default.htm on the Internet.

In addition, states can decide whether or not to require vaccinations prior to enrollment in schools or child care. Each state makes this decision individually. Information about specific state vaccine decisions is available from the National Network for Immunization Information (NNii) Web site at http://www.immunizationinfo.org/vaccineInfo/index.cfm#state on the Internet.

Should the vaccine be given to people who are already infected with HPV?

The preventive vaccines currently under study do not treat infections, although they have been found to be generally safe when given to women who are already infected with HPV. It is not feasible to pre-screen all women to see who has been exposed to the HPV types in the vaccines. At present, there is no generally available test to tell whether an individual has been exposed to HPV. The currently approved test only shows whether a woman has a current HPV infection and identifies the HPV type. It does not provide information on past infections. The decision to vaccinate or not, based on likelihood of prior exposure to these HPV types, is being discussed by ACIP and other advisory groups.

Should women who already have cervical cell changes get the vaccine?

The vaccine appears to be safe in women who have cervical abnormalities, but it is not known if the vaccine would help clear the abnormality. Women should talk with their health care providers about treatment for abnormal cervical cell changes.

Do women who have been vaccinated still need to have Pap tests?

Because the vaccine does not protect against all HPV types, Pap tests to screen for cervical cancer continue to be essential to detect cervical cancers and precancerous changes. In addition, Pap tests are critically important for women who have not been vaccinated or are already infected with HPV.

How much will the vaccine cost, and will insurance pay for it?

The cost of the vaccine is not known at this time. However, a Merck company cost-effectiveness analysis assumed a cost of $300 to $500. Individual or group insurance plans are subject to state laws. These laws generally establish coverage based on recommendations from the ACIP. Medicaid coverage is in accordance with the ACIP standard and immunizations are a mandatory service under Medicaid for eligible individuals under age 21. Medicaid also includes the Vaccines for Children Program (VFC). This program provides immunization services for children 18 and under who are Medicaid eligible, uninsured, underinsured, and receiving immunizations through a Federally Qualified Health center or Rural Health Clinic, or are Native American or Alaska Native.

What research is being done with HPV?

Researchers at NCI and elsewhere are studying how HPVs cause precancerous changes in normal cells and how these changes can be prevented. For example, a study to determine if a vaccine can prevent infection with HPV types other than those targeted by these vaccines and to better understand the mechanisms of action of the vaccines and factors that predict duration of protection is under way. NCI is conducting a large clinical trial of the HPV vaccine manufactured by GSK in Costa Rica , where cervical cancer rates are high. This study is designed to obtain information about the vaccine’s long-term safety and the extent and duration of protection. NCI is also collaborating with other researchers on therapeutic HPV vaccines that would prevent the development of cancer among women previously exposed to HPV. For use in the general population, the ideal vaccine strategy would combine a preventive and therapeutic vaccine.

Laboratory research has indicated that HPVs produce proteins known as E5, E6, and E7. These proteins interfere with the cell functions that normally prevent excessive growth. For example, HPV E6 interferes with the human protein p53, which is expressed by the p53 gene in all people and acts to keep tumors from growing. This research is being used to develop ways to interrupt the process by which HPV infection can lead to the growth of abnormal cells.

Researchers at the NCI and elsewhere are also studying what people know and understand about HPV and cervical cancer, the best way to communicate to the public about the latest research results, and how doctors are talking with their patients about HPV. This research will help to ensure that the public receives accurate information about HPV that is easily understood, and will facilitate access to appropriate tests for those who need them.

Source

National Cancer Institute

http://www.cancer.gov/